Galactic Garbage: The Debris Lost in Space

Outer space is getting crowded. Debris left by man-made technologies, traveling at astonishing speeds, could spell disaster for space missions and vital satellite services. Learn how we could solve the problem we created.

It’s a scene straight out of a sci-fi movie or a superhero film: on vast and remote farmland, an object falls from the sky.

For Australian farmer Mick Miners, it was not fiction but reality. The unpressurized trunk of the SpaceX spacecraft, dumped when it returned to Earth, wound up on his land.

Spaceflight has enabled man to explore beyond our blue planet. Today, satellites are vital for civilian needs and military operations. They help us track the weather, communicate with others, do business, and navigate our journeys. They enable military intelligence-gathering, air-traffic control, cartography, and surveying.

But these technologies, essential to life on earth, are contributing to a growing problem of trash in space.

The filthy frontier

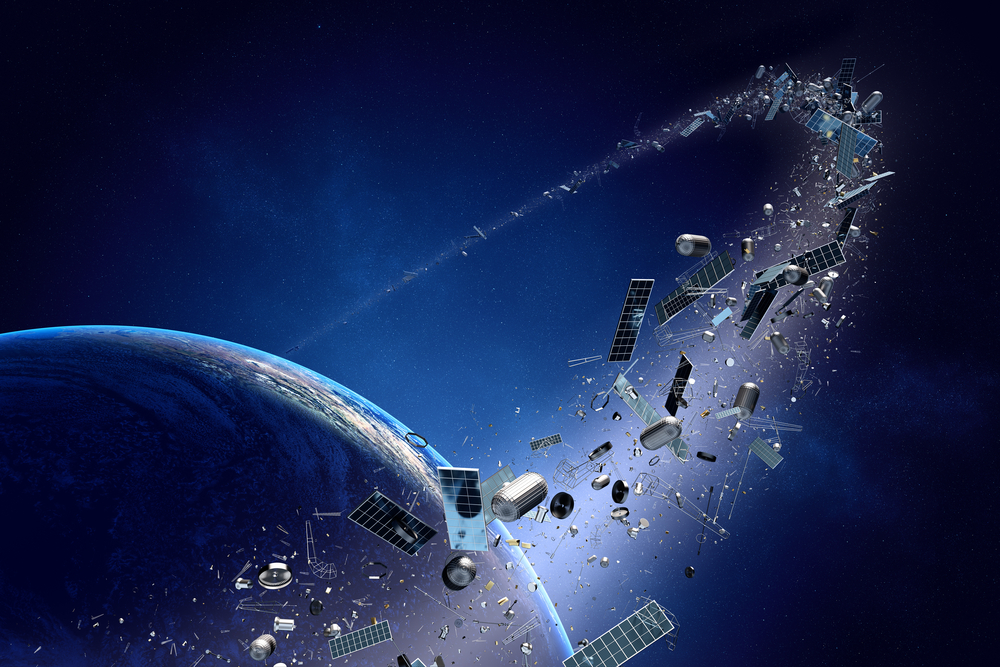

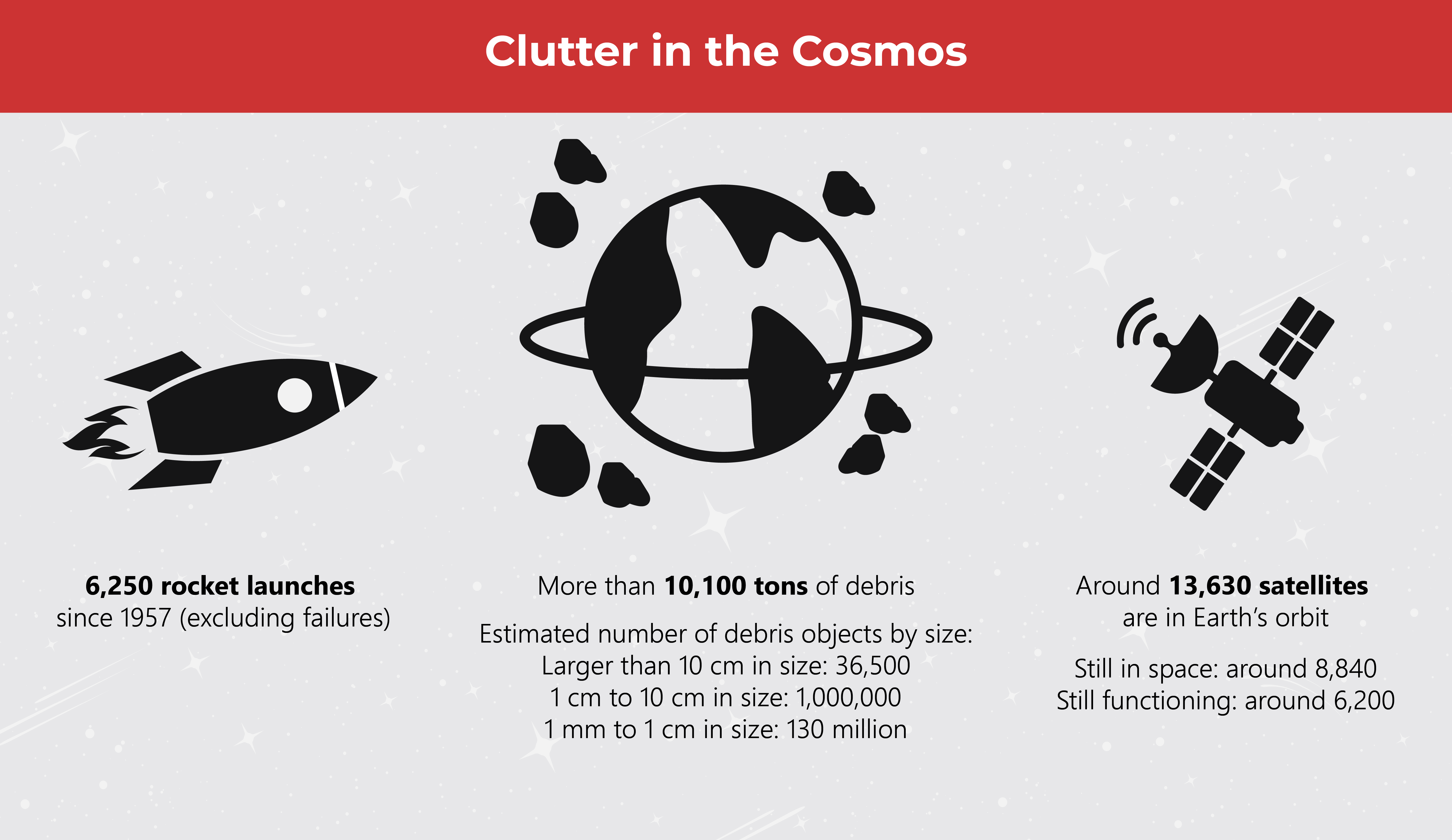

Orbital debris is any piece of machinery or debris left by humans in space. These objects can be as big as nonfunctional satellites and derelict spacecraft or as small as fragmentation debris or paint flecks. Since the space age began with the Sputnik 1 launch in 1957, more than 10,100 tons of debris are orbiting the Earth.

Space is the final–and increasingly filthy–frontier, and the latest figures on space debris compiled by the European Space Agency (ESA) paint a frightening picture.

On a collision course

Space debris orbits the Earth at astonishing speeds–more than 25,000 kilometers per hour. At that speed, a millimeter-sized fragment of orbital debris can damage satellites and spacecraft. In 2016, a tiny shard of debris chipped a heavily reinforced window of the International Space Station.

In 2009, two communication satellites–the defunct Russian Cosmos 2251 satellite and the American Iridium 33 satellite–crashed into each other. The collision, which occurred approximately 800 kilometers above Siberia, produced around 2,000 pieces of debris four inches or larger, plus countless tiny fragments.

It’s crowded in space–and it’s going to get much worse. Starlink, spearheaded by Elon Musk, has already launched over 2,000 satellites for global internet services and plans to launch 40,000 more. With Project Kuiper, Jeff Bezos of Amazon hopes to launch 3,236 satellites for a large broadband satellite internet constellation.

Could the stage be set for the Kessler Syndrome, a phenomenon named after Donald Kessler, a former NASA scientist? In a study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics in 1978, Kessler and co-author Burton Cour-Palais wrote, “As the number of artificial satellites in earth orbit increases, the probability of collisions between satellites also increases. Satellite collisions would produce orbiting fragments, each of which would increase the probability of further collisions, leading to the growth of a belt of debris around the earth.”

That belt of debris is here, and it’s growing. Even a place beyond the Earth’s atmosphere is not safe from man’s detritus. In the past, space was a race to claim many firsts. Today, we face a harder and more important challenge: clearing the battlefield.

The race to clean up space

According to NASA, space debris that orbits below 600 kilometers normally fall back to Earth within several years. But debris at an altitude above 1,000 kilometers could orbit the Earth for a century or more. As the costs of building and launching satellites continue to fall, companies and countries need to help stem the tide of trash in space.

Governments, companies, and industry stakeholders have come together to make space safer and cleaner. In 2002, the Inter-Agency Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) published the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines. The document gives recommendations on the design, operation, and disposal of space missions to prevent more orbital debris. In 2019, the Space Safety Coalition (SSC) published a document created by space stakeholders to promote best practices for the long-term sustainability of operations in space.

Startups and industry veterans are also stepping up.

Founded in 2013, Astroscale is a Japanese startup that develops innovative technologies for active debris removal services as well as in-orbit servicing. Its ELSA-d (End-of-Life Services demonstration) consists of two spacecraft: a servicer satellite and a client satellite stacked together. Equipped with a magnetic docking mechanism and proximity rendezvous technologies, the servicer satellite is designed to remove debris from orbit. The client satellite has a ferromagnetic plate to enable docking.

European aerospace company Airbus is part of the RemoveDEBRIS project, which was developed by a consortium of companies to test active debris removal (ADR) technologies. The project’s experimental spacecraft features three technologies for active debris removal: a deployable net, a harpoon to spear debris, and a drag sail to speed up deorbiting. The RemoveDEBRIS spacecraft is equipped with a Vision Based Navigation (VBN) system which uses 2D cameras and 3D LiDAR technology to verify debris-tracking techniques.

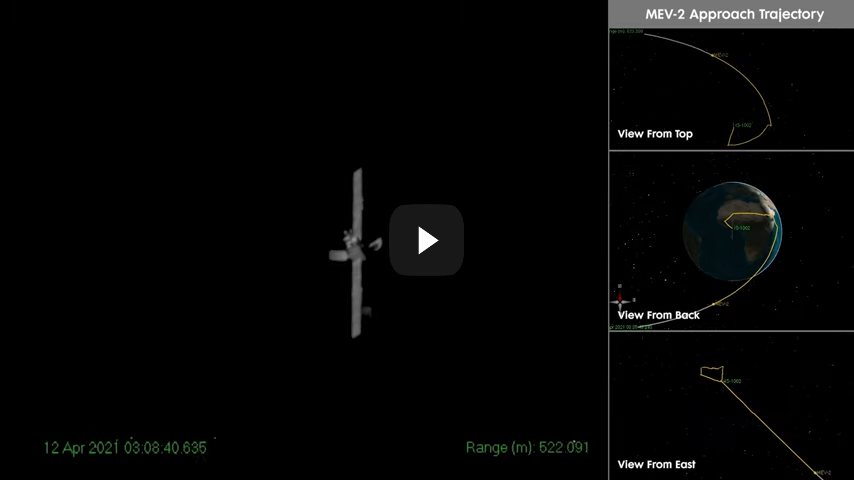

Northrop Grumman, an American aerospace and defense technology company, has developed technologies for space logistics. The Mission Extension Vehicle is designed to dock with geostationary satellites in need of refueling. Last April 2021, the Mission Extension Vehicle-2 (MEV-2) docked with the Intelsat IS-1002 communications satellite, which was running low on fuel. MEV-2 made it possible for the Intelsat communication satellite to stay operational for another five years instead of being decommissioned.

As one of the Top 19 EMS companies in the world, IMI has over 40 years of experience in providing electronics manufacturing and technology solutions.

We are ready to support your business on a global scale.

Our proven technical expertise, worldwide reach, and vast experience in high-growth and emerging markets make us the ideal global manufacturing solutions partner.

Let's work together to build our future today.